New Authoritarianism in Hungary at the beginning of the 21st century

The first part of this article deals with the emergence of „new authoritarianism” replacing “classic authoritarianism” in the first decade of the 21st century. In the second part we shall provide results of a study carried out concerning the recent developments of new authoritarianism. In the third part of the article an attempt will be made to reconstruct the path leading to the emergence of new authoritarianism in Hungary and the establishment of the illiberal system of national cooperation in 2010.

Old and new authoritarianism

„Authoritarianism” comes from the term „authority”, which refers to social relationship where power prevails. As Castells puts it, „power is the relational capacity that enables a social actor to influence asymmetrically the decisions of other social actor(s) in ways that favor the empowered actor’s will, interests, and values.” (Castells 2011:10). Authority, however, is a special kind of power referring to the ability to coerce based on the legal entitlement to do so. The state, consequently, has authority over its citizens, including the right to exercise violence against them.

The origins of authority can be traced back to the period when the state and the family were separated. According to Aristotle „the state is made up of households. Before speaking of the state we must speak of the management of the household. The parts of household management correspond to the persons who compose the household, and a complete household consists of slaves and freemen. Now we should begin by examining everything in its fewest possible elements; and the first and fewest possible parts of a family are master and slave, husband and wife, father and children. We have therefore to consider what each of these three relations is and ought to be: I mean the relation of master and servant, the marriage relation (the conjunction of man and wife has no name of its own), and thirdly, the procreative relation (this also has no proper name).” (Aristotle, Politics, 3.)

The father had the same kind of authority in the family as the king had in the state. It is not by chance that patricide and regicide have been treated in the Western monarchies as crimes of equal stand, both punished by utmost cruelty. Authoritarianism, consequently, as a readiness to suppress and being suppressed has been moulded into the family in order to train the individual to be the obedient subject of the state.

Obedience and submission, however, are behavioral patterns that are consequences of severe external and internal repression. The roots of authoritarianism are, of course, in the state, but authoritarianism would never have emerged without the family. As the authors of „The Authoritarian Personality” write, „…the effects of environmental forces in moulding the personality are, in general, the more profound the earlier in the life history of the individual they are brought to bear. The major influences upon personality development arise in the course of child training as carried forward in family life.” (Adorno et al. 1950: 6).

The „unholy alliance” between state and family resulting in the emergence of the authoritarian attitude has become a mass phenomenon in the modern nation state that, in order to legitimize its existence, needed to secure the consent of its citizens. Authoritarianism played an especially important role in legitimization in those states which were challenged by backwardness and were urged to catch up. Successful modernization was seen as a function of mass scale obedience of citizens who could be easily mobilized and directed.

Authoritarianism can be conceived as the interiorization of the state’s authority as a result of authoritarian child rearing practices carried out in the family. The formation of the authoritarian personality in the family occurs within the first decade of the person’s (mainly boy’s) life. Hierarchical, authoritarian, exploitative parent-child relationships may result in a type of authoritarian personality (Adorno et al. 1950: 482–484). Parents dominated by the state have a need for domination themselves. They frequently punish and rarely reward their children, demand unconditional obedience to arbitrary decisions and unexplained rigid rules. The rules and norms make the child's expression of aggression against the parents unimaginable, turning the feelings of resentment inward or toward external targets.

The result of authoritarian socialization is the development of a personality structure that serves as a complicated defense mechanism against the insecurity stemming from modernity (Fromm 1994). Striving for security, the authoritarian personality identifies him/herself with the party, the state, the church that seems to be invincible and powerful. The characteristics of authoritarian personality are conventionalism, projectivity, destructiveness and cynicism, authoritarian aggression, anti-intraception, superstition, obsession with homosexuality and promiscuity.

The major constituent of the authoritarian personality is the susceptibility to anti-Semitic ideology that at this “readiness level” can be seen as a set of utopian beliefs in a „perfect” society free of contaminating elements (jews, the disabled, homosexuals, communists, liberals etc.). Being destructive, authoritarian people act in good conscience. In reality, they can be considered as „criminals with a good intention.”

Contemporary realities of the state and the families clash severely with Aristotle’s claim that „the state is made up of households” and „before speaking of the state we must speak of the management of the household.” The fact is that due to the fast pace of modernization and globalization the power of the state over its citizens has withered away. International political and military organizations, multinational companies on the one hand, and the emergence of regional, local centers of power on the other hand, resulted in the disappearance of national sovereignity incapacitating the state to engender authoritarian identification of its citizens.

Aristotle would be surprised to find that nowadays in the West so many households cannot be characterized any more as units consisting of men in the roles of husband and father, and women as wives and mothers living together with their own children. In modern society the monopoly of the family in Aristotle’s sense has been replaced by a diversity of settings of private life. In the second half of the 20th century the family as the second pillar of authoritarianism also vanished (Hobsbawm 1995). Women have escaped from the prison of the household and become successful in settings other than the household.

In the second half of the 20th century states and families increasingly failed to perform the function of authoritarian socialization. Samuel Huntington characterizes the new, post-Cold War world as a multipolar and multicivilizational web of relations between people. According to Huntington, in the post-Cold War world the most important distinctions among people are not political but cultural. ”People define themselves in terms of ancestry, religion, language, history, values, customs and institutions.” (Huntington 2003: 21). Instead of identification with political communities, people in the 21st century identify with national cultural groups, tribes, ethnic groups, religious communities, and civilizations. The appearance of the „failed states” set forth the breakdown of authority, the intensification of „fault line” conflicts, the emergence of international criminal mafias, tens of millions of displaced people, the spread of terrorism, the prevalence of massacres, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, catastrophic deterioration of the environment, and the irresponsibility of the financial markets (Beck 2009). The appearance of „failed families” unleashed the “carpe diem” mentality, consumerism, and gave impetus to the development of “Erlebnisgesellschaft” (Schulze 1992).

Authoritarianism in its classic manifestation has lost the ground. Nevertheless, authoritarianism is still with us. Right wing extremism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia and homophobia are rampant throughout the Western world. The basis of the new authoritarianism, paradoxically, has been the disappearance of authority. Lacking the order provided by the nation state and the family, men and women have grown up with the post-Cold War experience, universal and undifferentiated anarchy that provides few clues for understanding the world, for ordering and evaluating events. The experience moulded by the post-Cold War world shows the image of chaos with deterring power. Consequently, the search for certainty in a world dominated by volatility and uncertainty has become the basis for new authoritarianism (Hankiss 2010).

One of the measures of new authoritarianism is an index showing the size of the group in a given polity that is on the “readiness level” to accept the message of anti-Semitism, anti-Gypsy sentiment, xenophobia and homophobia. The index of a country’s demand for right-wing extremism (DEREX) measures the rate of respondents who score high on at least three of the following four scales: prejudice, anti-establishment attitude, right-wing value orientation and anxiety (fear, distrust, pessimism). People scoring high on DEREX do not necessarily belong to the constituency of the far-right parties. “Attitude radicalism” is not identical with “political radicalism”. The vast majority of the new authoritarians support moderate right-wing parties. Nevertheless, in crisis the new authoritarians will not hesitate to opt for right-wing political forces who promise to create a New Order free of political strife and economic vicissitudes based on the equality of the “real” members of the nation.

The DEREX index shows the percentage of people identified as “attitude radicals” who are against liberal democracy and free-market economy.

The prevalence of new authoritarianism can be considered as a major source of destabilization of the society. Low levels of trust can render the capitalist system unable to function. Anti-establishment attitudes and economic nationalism spoil the investment climate. Xenophobia and aggressive nationalism endanger both domestic and international peace.

Right-wing extremists are rebellious against the social and political order of capitalism which they perceive as chaos and anarchy. They strive for a new order which provides equality, truth and justice.

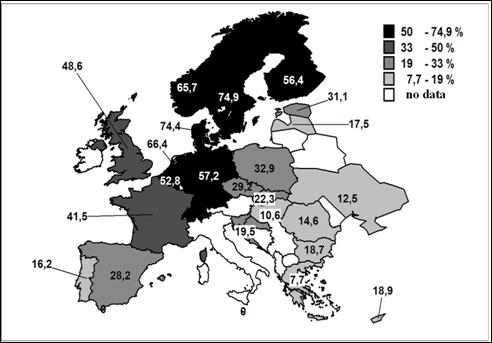

Map 1. Percentage of „attitude radicals” in European countries in 2010

(source: RiskandForecast.com)

Map 1 clearly shows the East-West slope of attitude radicalism in contemporary Europe. The proportion of “attitude radicals” is extremely high in Eastern European countries. New authoritarianism is less prevalent in the countries of Central and Southern Europe. Western European countries (including Germany) conspicuously produce low percentages of people of right-wing predilection.

The regions distinguished according to the prevalence of attitude radicalism in contemporary Europe demonstrate a ghostly correspondence with the three historical regions of Europe described so vividly by Jenő Szűcs (1983). In a study carried out on the 2008 datasets of the ESS similar regional distribution of typical value orientations was found. According to the value orientations three types were distinguished. The type of “sufferers” roots in the historical past of the East-Central and Eastern European regions. Those who chose to forgo the opportunities of an active life could only give an account of their own experience by using the passive voice. The sufferer’s narrative is that of the Eastern-European man of service who, when meeting his lord, would bow to the ground, kiss the hand of his lord or even throw himself down and kiss the hem of his lord’s garment (Szűcs 1983:141). Sufferers can be considered as predecessors of the new authoritarians. In contrast, creators are men (and women) of action, always ready to take a risk and face the challenges of the times. Rebels were found to refute the basic values of social existence.

Map 2 shows the individual European countries according to their share of “creators.” The proportion of “creators” is significantly higher in Western Europe, whereas in East-Central and Eastern Europe the ratio of “sufferers” is considerably higher.

Map 2. The proportion of “creators” in Europe by country in 2008

(source, Csepeli-Prazsák, 2010)

The map confirms that the borders of the three historical regions in Europe still exist. The map also shows that the individual’s autonomy that emerged in Europe in the 12th-13th centuries found home mainly in the countries of Western and Northern Europe. In contrast, in countries to the East of the Carolingian border creators are the minority. The same tendency prevails in countries of Southern Europe. The historical lack of the social networks identified by István Bibó as “the small circles of freedom” resulted in lasting consequences in the East-Central and Eastern regions of Europe (Csepeli and Prazsák 2010).

New authoritarians in Hungary

Selected issues of new authoritarianism were investigated in 2010 by the Social Conflict Research Center at the Faculty of Social Sciences of Eötvös Loránd University. In order to explore the patterns of thought characteristics towards new authoritarianism, a sociological survey was carried out. In the survey members of a national representative sample consisting of 1.000 people were questioned. Two subsamples were questioned as well. First, there was the subsample consisting of 100 members of a national radical paramilitary organization. Second, there was the subsample consisting of 100 members of an environmentalist civic organization. All respondents of all samples were questioned concerning social dominance, closed mind, locus of internal and external control, national identity, narratives of national history, and anti-Semitism and anti-Gypsy sentiments were investigated. In addition to the quantitative research, a qualitative research was carried out among the members of the national radical paramilitary organization.

Research results of the 2010 survey

In the 2010 survey, we aimed to identify the symptoms of a new type of authoritarianism as well as to describe the sociological factors and socio-psychological structures that organize and determine these symptoms. We summarized our findings in a volume published in 2011 (Csepeli et al. 2011).

In the present paper, we outline only the most relevant dimensions of the symptom-complexity that has been analyzed in detail. We selected these dimensions based on our conclusions formed by our research findings: 1. surveys applied by the "classic" Californian examinations found that anti-Semitism is the symptom of a "broader ideological framework" whose agent was labeled as an "authoritarian", "anti-democratic" and "irrational" personality. In our research we could also prove that the essence of prejudicial knowledge related to some social groups is not to be found in the prejudicial representation of those groups but the verification of category-based social inequalities. 2. We identified the source of new authoritarianism, the explanation for anti-democratic ideological worldview as an orientation of ethnicity-based social dominance, which accounts for a detailed analysis of our research results regarding social dominance included in the current paper.

Social dominance

According to Sidanius and Pratto the theory of social dominance is an interdisciplinary approach, a "coherent theoretical framework" that holds the various levels together (individual personality and attitudes, organizations, and social structure). They do not want it to be particularly identified as a psychological or sociological theory. The primary theoretical sources of social dominance orientation are varied (for example: authoritarian personality theory, Rokeach’s theory of political behaviour, Blumer’s group position theory, Marxism, neoclassical elite theories, political attitude studies, poll results, social identity theory, evolutionary psychology theories).

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), connected to social dominance theory, is attributed to individuals and legitimizes unequal and hierarchic social group interactions, moreover expresses judgement of group dominance (Sidanius and Pratto 1999). SDO corresponds to a general attitude orientation to intergroup relations, which approves or disapproves of the stratified nature of social intergroup relations. A high level of social dominance orientation corresponds to the reinforcement of hierarchy between groups while a low level of social dominance corresponds to the support of ideologies and policies which weaken hierarchy (Pratto et al. 1994).

We did not investigate research projects that were theoretically grounded and contained the SDO-scale, thus could neither validate nor verify the pronounced, authoritarianism-related conclusions of The Authoritarian Personality (TAP), for example, the explanatory force of child-rearing practices, psycho-analytical models or the pathological nature of the authoritarian mentality. On the contrary, empirical research has proven the existence of general ethnocentrism and the consistent relation of authoritarianism to dominance, repression and its positive correlation to political conservatism (Sidanius and Pratto 2005).

We modified the original SDO-scale in our examination, which has also been applied in multiple versions, so that it contained only those items that were proven adequate during our pilot studies. In the questionnaire we used 11 items from the commonly used version of the index.

The respondents had to express their level of agreement/disagreement related to certain statements with a five-point Likert scale. Table 1 contains the means of each Likert-item score.

Agreement on the first six statements (1-6) implies social dominance orientation, while disagreement on the same items means the non-existence of such orientation in the respondents. The next five statements (7-11) function in the opposite way: agreement expresses a desire for a society of equal members, while disagreement denotes a worldview where some may be in a socially-economically-politically disadvantaged situation as compared to others.

Respondents in the national adult sample refused the item "It’s OK if some groups have more chance in life than others" to the greatest extent. Besides, they accepted the item "All groups should be given an equal chance in life" the most. These opinions imply that the Hungarian adult population refuses the items favoring social dominance and accepts the items that reject the same phenomenon. In other words, social equality is a dominant value in current Hungarian society.

Public opinion polls carried out in Hungary have shown that equality is one of the most popular values in contemporary society. Moreover, the Hungarian obsession with equality is conspicuous in international comparisons as well (Tóth 2009; Roska and Tomka 2010).

The results of our study on new authoritarianism again demonstrate the perseverance of Hungarians’ obsessive egalitarianism. Comparing the average rates of agreements with the statements of SDO between the national sample and the two sub-samples, we found egalitarianism to be rampant in all the samples.

Table 1.

The average scores of agreement-disagreement with items concerning social dominance

(1-5 scale, 1: totally disagree, 5: totally agree, averages)

|

1.All groups should be given equal chance in life. |

4.4 |

|

2.No group should dominate in society. |

3.9 |

|

3.It would be good if groups could be equal. |

3.8 |

|

4.We would have fewer problems if we treated people more equally. |

3.8 |

|

5.We should strive to make incomes as equal as possible. |

3.7 |

|

6.Sometimes other groups must be kept in their place. |

3.0 |

|

7.In getting what you want, it is sometimes necessary to use force against other groups. |

2.6 |

|

8.To get ahead in life, it is sometimes necessary to step on other groups. |

2.5 |

|

9.Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups. |

2.3 |

|

10.It is probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bottom. |

2.2 |

|

11. It’s OK if some people have more chance in life than others. |

2.1 |

Two patterns of social dominance orientation

Averages, however, do not tell anything about the inner structure of attitudes determining orientation toward equality and inequality between social groups. In order to reveal hidden patterns of social dominance-orientation among the respondents, we used multivariate analysis. Two hidden patterns emerged from principal-component analysis. Both patterns concerned attitudes toward equality and inequality between social groups. The two patterns, though, differ according to the ideological nature of the argument justifying group inequality. The first pattern centred on the argument of collective inferiority and superiority. This argument is the key element of racial ideology. According to racism, the individual cannot do much to achieve his/her position in the social hierarchy, because they cannot resist to the genetic heritage stemming from his/her ancestry. Consequently, we believe that this pattern can be identified as the pattern of ethnic social dominance orientation (E-SDO). In contrast, the second pattern seems to be organized by the argument of equality of chances which is, as stated by Gellner, a principle of modern social organization (Gellner 1983). Belief in equality of chances opens the way for upward social mobility and reflects an orientation of social dominance in terms of class structure. Consequently, we identified the second pattern as the pattern of class social dominance orientation (C-SDO).

To describe the two types of social dominance we analyzed the responses in a way that depicts sample distribution per acceptance/refusal of ethnicity- or social class-based social inequality. We aimed to isolate those respondents that accept neither ethnicity-based nor social class-based inequality among the members of society. Compared to this group, others accept ethnicity-based inequalities but not the social class-based ones. The third case includes those that refuse ethnicity-based inequality but accept social class-based inequalities. Obviously, there will be others that accept both the ethnicity-based and the social class-based inequalities in society. The results of the cluster analysis that was conducted with the help of the C-SDO and E-SDO main components (the two types of social dominance) are described in the next table.

Based on our findings we can state that the majority of today’s Hungarian society accepts some type of social inequality. Those refusing both types of inequalities constitute a minority (38%), while one in five (19%) adult Hungarians accepts both of them.

Table 2.

The acceptance and refusal of class (C-SDO) and ethnic (E-SDO) dominance orientation

(clusters, cluster centers)

|

|

Refusal of both types of inequality |

Acceptance of both types of inequality |

Accept class-based inequality, refuse ethnicity-based inequality |

Accept ethnicity-based inequality, refuse class-based inequality |

|

E-SDO (pc) |

-0.81 |

0.82 |

- 0.64 |

1.06 |

|

C-SDO (pc) |

-0.78 |

1.00 |

1.19 |

-0.29 |

|

N (%) |

379 (38 %) |

193 (19%) |

163 (16%) |

249 (25%) |

Dogmatism

In the 1950s Rokeach developed a scale with which he measured the willingness for a close, rigid, uncompromising mentality that refuses arguments and criticisms, which is inseparable from authoritarianism (Rokeach 1960). The essence of this closed nature is anxiety that characterizes the lonely, defenseless and helpless members of society.

In our 2010 survey, we included twelve statements of the original one (To what extent do you agree with the following statements? Please, use the scholastic marking system! One means that you do not agree at all, five means that you completely agree.) The mean scores of each item are presented in parentheses.[1]

Both the means of individual items and the findings of further analyses confirm that Hungarians worry about the future. Fear of the future is so widespread that this item did not fit any of the components in the main component analysis of the 12 items.

The first type (main component) was named "romantic" as it includes items on heroism and greatness (item No. 10, 9, 12, 11). The second main component entails all elements of the classic "closed mentality" symptom (item No. 7, 5, 2). "Closed mentality" ensures a comfortable and stable position for people as truth is the exact opposite of non-truth (lies, mistakes) and the idea that the opponent may be right about some questions is entirely excluded. The third main component is "loneliness" that includes items on anxiety and some statements on its solution (items No. 8, 4, 6, 3).

National Identity (exclusion-inclusion, symbols, historical narratives)

Authoritarianism essentially predisposes of the rigid and emotionally intensive state of the exclusion of national origins. This eliminates various identities that are developed by different cross-categorizations, even if this is the person’s own identity or the identity of others that are in direct or mediatized relation to them. Studies researching authoritarianism both in Hungary and abroad found unequivocal correlations between authoritarianism and the exclusive, rigid, emotionally extreme positive experience of national identity (Blank 2003, Stone et al. 1993, Fábián 1999, Enyedi et al. 2002). According to the academic literature that empirically describes national emotions and mentalities, there exist numerous variations between the two extremes of national identity, and identifying these is possible only if we know the boundaries between naturally existing patterns of national identities and the extremist, exclusive ones (Dekker and Malova 1995, Csepeli 1992).

While preparing our examination, we aimed to differentiate the natural, “patriotic” variation of national feeling from the obsessive, exclusive, "chauvinistic" ones so that we can analyze how the existing variations correlate with the authoritarianism characteristics described above.

Identification of Hungarians

"Citizens" in East-Central European national discourses do not constitute a separate dimension (Bibó 1986, Hroch 1985). As far as East-Central European nations are concerned, the content of "citizenship" is overwritten by "ancestry" and "native language," and if we combine the latter ones we get an exclusive rather than inclusive interpretation of nationality. Our findings confirm the same phenomenon, as Hungarian adults prefer the traditionally cultural-national elements when asked to indicate items for categorization of Hungarian nationals. These elements, however, determine not by choice but by fate whether someone is Hungarian or not. Self-categorization and immigration, both serving as categorizing criteria, were much less frequent.

Hungarian identification

While analyzing the affective and cognitive elements of national identity, we aimed to differentiate between its "patriotic" and "chauvinistic" variations. The twenty possible criteria of national origin (Dekker and Malova 1995) correlated with the dimensions described by Csepeli’s model (Csepeli 1992).

Based on a multi-variable analysis to handle together all statements ranging from the natural national feelings of our everyday lives to extreme nationalist items, we identified two types of nation-concepts. The inclusive type contains affective elements that are close to the cultural-national preconceptions about Hungarians. The love of Hungary, pride over the country and emotions related to Hungary and the Hungarians are the most dominant, which are followed by the love of Hungarian language. Hungarian citizenship as a source of pride is also part of the inclusive nation-concept, which implies that citizenship is not only a legal but also an emotional identity-forming category in the Hungarian nation-concept, contrary to the classic nation-state model. We consider our main component a tool for measuring the inclusive nation-concept as it has no element that would exclude anybody that considers themselves Hungarian from the community of Hungarians. What is more, this view emphasizes that there is nothing better than to be Hungarian. In this case, national identity is determined by the emotional identification with the internal values of Hungarians rather than the separation from or segregation against other nations. However, this is not the case with the other main component, which entails all elements that express the geographical or cultural segregation of Hungarians, that is, by accepting these items, it implies a double negation: Hungarians are not "non-Hungarians." The major factor of the exclusive nation-concept is the separation from other nations. The followers of this originally closed exclusive nation-concept think that Hungarians that mix with others, do not live in Hungary or prefer to meet people from other countries are not true Hungarians. The nation’s "purity" is also part of this cognitive structure, as supporters of this view think that non-Hungarians should move away from Hungary.

National symbols

Symbols play an important, non-substitutable role in every nation’s life, as they represent the nation as an emotional community for both the insiders and outsiders of that nation. The integrating power of each symbol depends on the degree to which they are able to activate the "cognitive archeological" layers stored in collective narrative memories.

In our 2010 survey, we listed twelve national symbols and asked respondents to rate how much those items symbolize Hungarians. Based on these symbols being refused or accepted we could identify different levels of uniformity among Hungarians. The National Anthem, the national flag, the coat of arms, the Holy Crown and Szózat, which may be considered as the second national anthem, are broadly and uniformly accepted. However, the items listed at the end of the table are less accepted and more divisive at the same time, the standard deviation (polarization) of the opinions on these items was the highest.

With multi-variable analysis (main component analysis), we examined opinions on the national integrating power of each symbol and identified three different cognitive patterns.

The "narrative" pattern includes those symbols whose powers are primarily found in the text itself that was able to transmit the message of collective feelings beyond the inherent logic through generations and generations. The most dominant element of the "narrative" pattern is the acceptance/refusal of the 1849 Declaration of Independence as a national symbol.

The "Gemeinschaft" (community) pattern incorporates those symbols into one single dimension that focus on the feelings of historical community and belonging together, obviously without the sense of rationalism. The code of these symbols (colors, animals) are typically analog, although the natural signs applied had lost their meaning in contemporary national identities. The most essential element of this cognitive pattern of accepting or refusing the “Gemeinschaft” symbols is the map of the historical

Greater Hungary and the turul bird.

The "modern" pattern contains national symbols that are also used contemporarily (though currently changing) but originally referred to the past, similarly to the symbols of the “Gemeinschaft” pattern. The difference between the two patterns is that the official national liturgy has taken over the symbols of the "modern" pattern, while the "Gemeinschaft" symbols are common among the followers of the national oppositionist subculture.

Discrimination and intolerance (anti-Semitism, anti-Gypsy sentiment)

To describe intergroup discrimination, we included two target groups of anti-Semitism, Jews and Gypsies, which are the largest and most rejected ethnic minorities. We included the names of these two minorities in different contexts and examined social distance and stereotyping separately, which constitutes an integral part of authoritarianism symptoms.

Social distance

Similarly to most empirical research conducted in Hungary, we measured social distance with a simplified Bogardus-scale. The acceptance of Gypsies is lower than that of Jews in all three stages. At the same time however, the refusal of Gypsies is significant only in the category of "partner" (76%), with the largest difference in favour of Jews, whom are refused by 59% of the Hungarian population as a partner.

Table 3.

Social distance from Gypsies and Jews

(% of acceptors)

|

Gypsies |

Jews |

|

|

Partner |

24 |

41 |

|

Neighbor |

61 |

73 |

|

Colleague |

69 |

77 |

Prejudice and stereotypes against Gypsies

It is difficult to differentiate between prejudice and stereotypes related to collective images of a group of different people. If that image is related to the appearance or spiritual-mental construction of a group, we are talking about stereotypes. If we notice prejudice, the motivational element is emphasized, which is used to verify a highly generalizing, not very informative cognitive element.

Of the three stereotyping, prejudicial statements against Gypsies, respondents agreed most about the following: "most Gypsies do not learn to respect property in their families." Agreement to this item could be marked on a five-point scale, where five was given by those that think Gypsies can be characterized by the "burglar" stereotype that is well-known from other research findings (Csepeli 2010). The mean value of agreement was 3.9. The second statement ("Gypsies are born to be criminals.") has only a slightly lower mean of 3.4. Contrary to the two accusing statements ("burglar", "criminal"), the third one uses reverse logic, as it exonerates Gypsies: "poverty forces Gypsies towards criminal behaviour." Taking into account the results of the first two statements, it is not surprising that this last item was rather rejected (2.3).

Gypsy-phobia

Half of the respondents (53%) agreed with the general anti-Gypsy discourse ("Gypsies often intimidate peaceful people."), while 38% disagreed with the same item. The mean on a five-point scale was 3.7.

Political anti-Semitism

One point of the 1944 program of the Hungarist Arrow Cross Party was “Free Hungary from Jews.” 13% of our sample that is representative of the adult Hungarian population agreed with this extreme claim. As a result, it is not surprising that one of the extreme political items – one reason for Hungary’s decline is “the exploitation by Jewish capitalists” – got supported rather than refused (the mean was 2.07 where 1 is completely disagree and 3 is completely agree).

The 1944 Jewish persecution (The Holocaust) was included in the list of Hungarian national tragedies, in which we asked respondents to categorize items as being part of the greatest tragedies of Hungarian history or not. According to 64% of the respondents, the Holocaust is not among the three most important national tragedies.

Extreme political anti-Semitism

We considered the acceptance of the "Free Hungary from Jews" program point and, at the same time, agreement to the idea that Jews were also responsible for their deportation and ghettoization in 1944 as the indicator of the most extreme political anti-Semitism. 70% of the nationally representative sample disagreed with both statements. 18% agreed with one of the statements above and 3% agreed with both, an implication of political anti-Semitism.

The Hungarian Road to New Authoritarianism (1989-2012)

The events of the „annus mirabilis” changed the life of the citizens of Central and Eastern Europe. Moreover, the collapse of the Soviet Union made the Cold War international system history. The people of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were exposed to the challenges of a multipolar and multicivilizational world living on the periphery of the West (Bernhard and Kubik 2013).

Passive voice

The transition from state socialism to liberal democracy and market economy was quick and unexpected. The experience of the transition in Hungary was dominated by the legacy of the “passive voice” that made impossible to interpret the revolutionary events in terms of collective achievement. Instead, the experience of change was like the experience of a weather change.

In attribution to changes of lasting consequence, Hungarians had been historically conditioned to look for stable external causes such as fate and interventions of foreign powers. Responsibility, risk taking and achievement as a result of rational calculation are alien patterns of attribution among Hungarians. The momentum of the collapse of state socialism was experienced as a surprise. There were no viable explanations available for the people.

Change of frame of reference

Nevertheless, the transition from state socialism to liberal democracy and market economy resulted in mass dissatisfaction (Pataki 2013). Dissatisfaction was engendered by the sudden change of frame of reference. Before the transition, Hungarians compared themselves to the cluster of peer countries in the Central and Eastern European region called the “socialist camp.” As a result of the comparison, Hungarians felt as if Hungary was the “happiest barrack of the socialist camp.” Right after the transition, due to the unrealistic expectations concerning the transition to capitalism, Hungarians changed their frame of reference and compared themselves to the core capitalist countries of Western Europe such as Austria, Germany or France. As a result of the new comparison, Hungarians suddenly found themselves living “in the saddest shopping center of the West.”

Existential insecurity

The public dissatisfaction stemming from the transition from state socialism to liberal democracy and market economy cannot be attributed solely to the change of the frame of reference. In fact, there were more important factors contributing to the sense of popular frustration and deprivation in the Hungarian society. First and foremost we have to mention the loss of existential security.

Two major changes occurred and neither of them had been experienced during the 40 years of state socialism. As a result of the collapse of the state socialist industry, one and a half million workplaces ceased to exist. The agricultural cooperatives were demolished. As a consequence, hundreds of thousands of former members of the cooperatives lost their earnings immediately. Unemployment, which had previously been unknown, became a daily experience and a source of threat. Free enterprise had also been unknown under state socialism. The new entrepreneurs, however, had to face the risks of enterprising and many of them failed. Only the pensioners and the employees in the public sectors could feel secure.

Epistemological insecurity

In addition to existential insecurity the transition to liberal democracy and market economy brought about epistemological insecurity as well. During the decades of state socialism there could not be much doubt concerning the truth. There were true believers on both sides of the state socialist system. There was a clear dividing line between truth and lie. Both sides thought that that the other side is living in lie and that they themselves live in truth. Vaclav Havel’s message was strong and straightforward: the Communists live in lie and the Opposition lives in truth (Havel 1990).

The diversity of viewpoints surfacing in the free media made the belief in truth and lie untenable. Heroes became villains, and villains became heroes. People became disoriented having been exposed to competing ideologies. The age of certainty was replaced by the age of confusion. Unfortunately the basis of the transitions, the concept of democracy became prey of confusion. The people in Hungary (as well as in the other Eastern and Central European countries) by democracy meant a system brought about through free and fair elections. Democratically elected regimes, however, lacking the controling and balances created by the constitution, are tempted to ignore the limits of their power and deprive their citizens of basic rights and freedom (Zakaria 1997).

Sense of social injustice

Dissatisfaction with the new system created in 1990 would not have been so profound without the experience of social injustice caused by the rise of social inequality. Paradoxically enough, the sociological evidence does not support the popular perception of the unparalleled rise of inequality (Keller and Tóth 2011). People, however, do not read sociological surveys. Instead, they rely on their everyday experience and are shocked by the simultaneous sight of poverty and wealth. The stratification surveys, however, do not reveal that the cause of ressentiment is the perceived gap between the poor and the rich but the lack of justification. Sociological surveys dealing with the perception of social justice demonstrate that especially in Hungary there are no viable patterns of justification making social inequality legitimate (Örkény and Székelyi 1998).

Social distrust

As a result of the prevalence of the sense of social injustice the people in the Hungarian society are unable to interact and communicate with each other in terms of tolerance, cooperation and social trust. Results of the subsequent studies carried out in the framework of ESS and EVS show high levels of distrust, intolerance, xenophobia and anomie among Hungarians compared to the inhabitants of other European countries (Tóth 2010) Civil society, severely regressed during the four decades of state socialist rule, has never been able to recover in the climate of social distrust (Miszlivetz 1999).

Failure of the economy

During the 20 years of transition the Hungarian economy has been unable to produce steady growth based on added values created by the Hungarian workforce. The growth has been based on FDI that resulted in unequal territorial and social development. Moreover, public spending aimed at even the inequalities has resulted in immense deficit of the state budget.

Clashing historical narratives

Being unable to understand and explain malignant association of the economic stalemate and the social inequality perceived as scandalous, the Hungarian public discourse has resorted to the discussion of historically well known but never solved conflicts stemming from the past and this has seemed in Hungary not to pass. Hungary as an independent nation state did not exist from 1526 to 1918. The Hungarian state, declared independent and recognized internationally, was perceived by the citizens as a truncated version of the Hungary which they wished to see on grounds of historical claims. The treaty of Trianon, which created the national independence, was seen by Hungarians as a source of mourning and shame. In order to preserve the stability of the socialist camp no word had been allowed to be raised against the Trianon treaty, whereas it continuously had been perceived as an act national injustice.

No wonder the critical voice concerning the Trianon treaty was to be heard immediately after the transition. Instead of being the prime minister of ten million Hungarian citizens living on the territory of the Hungarian Republic, József Antall claimed to be the prime minister of fifteen million Hungarians living on territories of the neighbouring countries as well.

As the failure of the transition to capitalism became apparent, the appeal of the “Trianon narrative” intensified. The “Trianon narrative”, however, cannot be separated from the “Holocaust narrative”. Hungary was an ally of Germany in WW II. The two countries fought and lost together. Due to the alliance with Hitler’s Germany some territories which had been lost following the treaty of Trianon were returned (Pastor 2013). The population of the new citizens of the enlarged Hungary consisted of ethnic Hungarians, Jews, Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, Slovenes and Croats. Jews, unfortunately, were subject to the anti-Jewish legislation that deprived them of their rights provided for them since 1869. When Hungary was occupied by its ally on March 19, 1944, within six weeks the Hungarian state authorities were ready to deport hundreds of thousands of Hungarian citizens classified as Jews to annihilation camps (Braham 1998).

Many of the deported Jews lived on territories returned between 1938 and 1941. For the Hungarians classified as non-jews, however, these were the cheered years of the revision of the hated Trianon treaty. The “Trianon narrative” and the “Holocaust narrative” consequently clashed. The “Trianon narrative” ignores the responsibility of the Hungarian society for the Holocaust, and cheers the revision of the Trianon treaty while the “Holocaust narrative” ignores the revisionist claims and blames the Hungarian state and society for sending almost half a million Jews into death camps.

Political and ideological polarization

The two clashing narratives correspond to two present-day political and ideological camps which are unable to communicate with each other. Moreover, there is no middle between the political right and the political left.

The radical and the moderate wings of the political right are both favoring the “Trianon narrative” and oppose the “Holocaust narrative”. The majority of the right, consequently, depends on the consent of both wings. In order to maintain the majority Prime Minister Viktor Orbán never misses the opportunity to court the radical right wing voters. On September 29, 2012 he gave a speech on the occasion of inauguration of the statute of the mysterious Turul bird. In his speech he repeated the most favored topics of the “Trianon narrative”. “„The Turul is an archetype for Hungary. We are born into it in the way we are born into our language and history. It’s an archetype incorporated in our blood and our native soil. When we are born as Hungarians, our seven tribes bond by blood, our king Saint Stephen founds a state, our troops loose a battle of Mohács, while the Turul-bird acts as a living symbol for Hungarians alive, dead, and yet to be born.”

Anti-Semitism, as we have seen, however, is not the issue of primary importance for the new authoritarians. More important is the problem of the Roma minority that due to the social psychological laws of illusory correlation seems to be a homogenous group consisting of criminals, parasites, alcoholics and drug addicts. The extreme right wing political discourse exploits the disturbances caused by the presence of the Roma underclass living in ghetto-like villages.

Losers and winners of the transition

During the transition years between 1990 and 2010 the losers of the transition continuously outnumbered the winners. Results of public opinion polls carried out recently have shown that 67 % of the respondents of the national representative sample categorized themselves as “losers” of the transition. The self-classification of ‘loser’ makes varieties of misattribution of the failure possible, such as blaming other groups (Jews, capitalists, Gypsies, entrepreneurs or Communists). Personal responsibility, internal locus of control and the need for achievement are not taken into account in explaining the loser’s position (Csepeli et. al 2011).

Lost illusions

There was a moment of hope in 2004 when Hungary in the company of other countries joined the European Union. By January 1, 2007 all countries of the Central and Eastern European Region had obtained access to the European Union. The borders between the countries ceased to be obstacles to everyday travel. The accession was considered by the peoples living in Central and Eastern Europe as a moral compensation for their alleged services in defense of the Western Europeans against Tartars, Turks and Soviets. The enlarged Union, however, has not fulfilled the exaggerated expectations.

The money provided by the structural and cohesion funds of the European Union had no effect on economic growth. Much of the money was wasted on unnecessary investments such as building new spas, rolling city towers or dog shelters. Restrictions in countries of Western Europe made the free mobility of the working people difficult.

Democracy without democrats

I n fact, the period between 1989 and 2010 can be characterized best as the transition from liberal democracy to illiberal democracy. Hungarians built a political system that accords with the commonsense view of democracy. There have been in every fourth year competitive, multiparty elections. Democracy, however, cannot function without democrats. There were no attempts to institutionalize democratic political education transforming subjects of the state to citizens (Csepeli et al. 1994). Citizens, as opposed to subjects, are concerned with the protection of the individual’s autonomy and dignity against the psychological or physical coercion of any authority, whatever it is, state, church or party. Hungarians created a democratic system without democrats who would care not only about the procedures of selecting representatives to govern but also goals for government. The position of democrats rests on the traditions beginning with the Romans in the Western region of Europe. This is the kind of democracy that human beings have certain unalienable rights that no government can ignore. According to Zakaria the Magna Carta, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, the American Constitution and the Helsinki Final Act are all expressions of constitutional liberal democracy (Zakaria 1997).

The failure of political socialization

One of the paradoxes of the research of political socialization over the past twenty years is that the younger generation do not reject the fundamental democratic values but they rather reject political parties and politicians (Csákó, 2011). For them most important is that the individual’s, that is, their own rights are respected and least important for them is that others’ rights or the rights of minorities are respected. They do not understand this contradiction: how could the observation of our personal rights be expected when, parallelly, we ourselves consider it least important that other people’s rights or the rights of minorities are observed. They consider the ability and possibility to influence political decisions less important and the fundamental importance of the factor defining the quality of the system of democracy is completely unknown to young people. This phenomenon also shows that the attachment to the most important value has not been formed among the Hungarian younger generation, which should be formed in the process of political socialization.

The rise of national socialism

State intervention aimed at helping the winners of the transition has failed. Finally, the frustrated mass of losers in 2010 elected representatives of a political party who publicly opposed the principles of liberal democracy and market economy. The new government immediately heard the voice of the masses demanding a strong state that promotes security, equality and excludes foreign influence. The government has posed as freedom fighter defending national interests against the IMF and the EU.

The legacy of post-socialism has proved to be strong enough to endure especially among people who have lost their existential roots as a result of the transition to market economy. Disenchantment with capitalism for these people was caused by the loss of their existential base that could not have been compensated with the new freedoms.

The Basic Law of Hungary with its ambiguous Preambulum does not fit into the pattern of constitutional liberalism. This Law replaced the Constitution of the Hungarian Republic accepted in 1989. The acceptance of the Basic Law marked the end of the liberal era in Hungary. The majority of the voters striving for truth and justice assisted in the creation of the Basic Law that ignores the rule of law, the separation of powers and the protection of basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion and property. The democratically elected Parliament with a two-third majority replaced the liberal Constitution with the Basic Law that is in contradiction with the “real existing democracy” (Schmitter 2007). Experimentation to improve the “real existing democracy” had no sense any more (Csepeli and Muranyi 2011).

National absolutism

As a result of the elections held in 2010 Hungary became a party-state. The democratically elected regime quickly eliminated the system of liberal democracy replacing it with the illiberal system of national absolutism. The new Basic Law openly ignored the rule of law and the separation of powers. The basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion and property were restricted. Ethnic nationalism was reinstated granting the Hungarian citizenship for citizens of the neighboring countries. Dual citizenship with the right to vote married two different national identities. The ethnic identity stems from the pattern of cultural nation while the political identity is based on the pattern of the political nation. Hungarians being citizens of foreign countries were given the right to become citizens of Hungary without the requirement to move into Hungary.

The regime of national absolutism identified itself as the System of National Cooperation that seems to rest on Fascist tradition. The SNC produced a new stratification of the society. In the centre there is the First Person and its Court. In the next eschelon there are the Estates and Councils whose members are selected by loyalty and not by competence and expertise. The First Person regularly consults with the people by sending them questionnaires by direct mail. Everyone has a place in the resulting database. Those who have sent back the questionnaire to the First Person will be registered as the People. Those who dared not to send back the questionnaires will be criminalized and marginalized.

National absolutism rests on nationalization of the major sources of economic power such as energy, ICT and the banking sector. If nationalization is not possible, national capitalists are preferred to foreign “hawk” capital.

SNC has devoured the schools, the institutions of higher education, the hospitals and the museums. The ideological basis of the SNC is national socialism fuelled by etatism and populism.

Problems to be solved

Three major problems stem from the misdirected transition process. In case these problems remain untreated or continue to be in the captivity of populist discourse there will be not much room for rational approach.

Inequality

The art of public policy is to find the proper balance between equality and inequality in the society. Excessive equality can result in disincentive effects on achievement. Excessive inequality can lead to the development of unbearable social climate.

The public policy dealing with inequality should be complex and unaffected by bureaucratic aspects. Unemployment, mismatch of skills and demand, lack of territorial mobility should be addressed simultaneously.

Ethnic tension

The level of tension between the Roma and non-Roma population has become unbearable in some regions of the country (especially in Northern Hungary). Cultural roots of the conflict should be explored from both sides. Due to the extreme diversity of the Roma population individual action plans should be set forth in each micro-region. Long term solution can be expected as a result of a comprehensive, customized, ICT centered life-long education system.

Civic education

In order to create in Hungary a “really existing democracy” democratic citizens should be trained. Democrats are able to and ready to protect the inalienable rights of the individual. The canon of democracy should be introduced into the public education. The canon of the classic Hungarian liberal tradition is worth teaching. The canonical figures include István Széchenyi, Lajos Kossuth, József Eötvös and István Bibó (Gerő 1999). The subject of civic education must include the works of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu, John Stuart Mill and Isaiah Berlin.

These problems share the common characteristics of not being treated properly in the past by the political decision makers. If these issues continue to be untreated, the crisis will continue.

Literature

· Aristotle: Politics, Book 3. Source: POLITICS by Aristotle. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Original URL: http://www.constitution.org/ari/polit_00.htm Original date: 1997/9/25 -Last updated: 2011/10/25.

· Adorno, T. W., Brunswik, E.F., Levinson, D.J. Sanford, R., Nevitt, R. (1950) The Authoritarian Personality. New York, London: Norton and Company.

· Beck, U. (2009) World at Risk. London: Polity Press.

· Blank, T. (2003) Determinants of National Identity in East and West Germany: An Empirical Comparison of Theories on the Significance of Authoritarianism, Anomie, and General Self-Esteem. In Political Psychology Vol. 24, No. 2. 259-288.

· Braham, R. L. (ed.) (1998) The Nazis Last Victims. The Holocaust in Hungary. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

· Castells, M. (2011) Communication Power. OUP Oxford.

· Csákó, M. (2011) Youth, School and Democracy in Hungary. In: Central European Political Science Review, Vol. 12, No. 44. 117-144.

· Csepeli, Gy. (1992) Nemzet által homályosan. (Vaguely by the Nation). Budapest: Századvég Kiadó.

· Csepeli, Gy., German, D., Kéri, L., Stumpf, I. (eds.) (1994) From Subject to Citizen. Budapest: MTA PTI.

· Csepeli, Gy. (2010) Gypsies and gadje. The perception of Roma in Hungarian society. In : Central European Political Science Reiview. Vol.11. No. 40. 62-78.

· Csepeli, Gy., Murányi, I. (2011) Experimental Democracy Research. Society and Economy 33, no. 2 : 407 - 412.

· Csepeli, Gy., Murányi, I., Prazsák, Gergő (2011) Új tekintélyelvűség Magyarországon. (The New Authoritarianism in Hungary ) Budapest: Apeiron.

· Dekker, H., Malova, M. (1997) Nationalism and its explanations. Paper presented at the first Dutch-Hungarian Conference on Interethnic Relations. Wassenaar: NIAS.

· Enyedi, Zs., Erős, F., Fábián, Z. (2002) Authoritarianism and Prejudice in Present-Day Hungary. In: Karen Phalet and Antal Örkény (eds.) Ethnic Minority and Inter-Ethnic Relations in Context: A Dutch Hungarian Comparison. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002, 201-215.

· Fábián, Z. (1999) Tekintélyelvűség és előítéletek (Authoritarianism and Prejudices) Új Mandátum, Budapest.

· Fromm, E. (1994) Escape from Freedom. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

· Gerő, A. (1999) Hungarian Liberals. Budapest: Új Mandátum.

· Hankiss, E. (2010) Life Strategies in the Age of Uncertainty. (presentation)

· Havel, V. (1990) Living in Truth: 22 Essays Published on the Occasion of the Award of the Erasmus Prize to Vaclav Havel. (Edited by Jan Vladislav)

· Hobsbawm, E. (1995) The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914–1991. New York: Pantheon.

· Huntington, S. (2003) The Clash of Civilization and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schister Paperbacks

· Keller T., Tóth I. Gy. (2011) Income distribution, inequality perception and redistributive claims in European societies. GINI Discussion Paper 7. Amsterdam, AIAS.

· Kubik, J., Bernhard, M. (eds) (2013) Twenty Years After: 1989 and the Politics of Memory. (anticipated completion of the manuscript: spring 2013).

· Miszlivetz, F. (1999) (edited by Jensen, J., Pogácsa, Z.) Illusions adn Realities. The Metamorphosis of civil sociedty in a New European Space. Szombathely : Savarai University Press.

· Örkény A., Székelyi M. (1998): Igazságosság és legitimáció. Rendszerváltás után trendek Kelet-Európában. (Social Justice and legitimation. Trends followoing the change of the system) in: Társadalmi Riport 1998, Kolosi Tamás, Tóth István György, Vukovich György (szerk.). Budapest: TÁRKI, 549–571.

· Pastor, P. (2013) Review Article: Inventing Historical Myths-Deborah S. Cornelous, Hungary in World War II. Caught int he Couldron. New York: Fordham University Press. 2011. E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 5 (2012): http://ahea.net/e-journal/volume-5-2012.

· Pataki, F. (2012) A varázsát vesztett jövő. (The lost magic of future). Budapest: Noran Libri.

· Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Lisa, M. Stallworth, L.M., Malle, B.F. (1994) Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 67. No. 4, 741-763.

· Rokeach, M. (1960): The Open and the Closed Mind. Investigations into the nature of belief systems and personality systems. New York:Basic Books.ch.4. The Measurement of Open and Closed Systems. 71-108.

- Rosta, G., Tomka, M. (2010): Mit értékelnek a magyarok? Az Európai Értékrend vizsgálat 2008. évi magyar eredményei. (What do Hungarians appreciate most? Hungarian results of the European Values Study in 2008). Budapest: OCIPE-Faludi Ferenc Akadémia.

· Schmitter, P.C. (2007) Political Accountabiilty in “Real-Existing Democracies”: Meaning and Mechanisms. Firenze: Instituto Universitario Europeo.

· Schulze, G. (1992): Die Erlebnisgesellschaft: Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

· Sidanius, J., Pratto, F. (1999): Social Dominance. An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppresson. Cambridge, 1999, Cambridge University Press.

· Stone, W.F., Lederer, G., C. R. (eds.) (1993.) Strength and weakness: The authoritarian personality today. New York: Springer-Verlag Publishing.

- Szűcs, J. (1983) The three historical regions of Europe. Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 29 /1983/ 131-184.

- Tóth, I. Gy. (2009): Bizalomhiány, normazavarok, igazságtalanságérzet és paternalizmus a magyar társadalom értékszerkezetében. A gazdasági felemelkedés társadalmi-kulturális feltételei című kutatás zárójelentése (Lack of trust, sense of social injustice and paternalism as constituents of the value structure of contemporary Hungarian society. Final report of research on social and cultural conditions of the rise of the Hungarian economy.). TÁRKI, Budapest.

· Tóth, I., Gy. (2010) A társadalmi kohézió elemei: bizalom, normakövetés, igazságosság és felelősségérzet- lennének. (Lacking elements of social cohesion: trust, adherence to norm, sense of justice and sense of responsibility In: Kolosi Tamás – Tóth István György (szerk.): Társadalmi Riport 2010. Budapest, TÁRKI, 2010, 254–287.

· Zakaria, F. (1997) The Rise of Illiberal Democracy. Foreign Affairs. Nov/Dec. 76. 6. 22-43.

[1] Items on the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale. No.1. It is not surprising that people are afraid of the future nowadays (4.00). No.2. People either stand on the side of truth or not (3.44). No.3. Social advancement is connected to our glorious and forgotten past (3.21). No. 4. In order to find our way in the world, we have to trust the leaders (3.10). No. 5. A political bargain usually means the betrayal of our initial point of view (3.04). No. 6. Man in itself is a helpless and miserable creature (2.74). No.7. From the various world views only one can be true (2.63). No.8. The world we live in is a very lonely place (2.44). No.9. It is better to be a dead hero than a living coward (2.44). No.10. If someone does not believe in a greater cause, he had better die (2.23). No.11. Even violence is acceptable if it serves a noble idea (2.21). No. 12. I would rather be a „big man” than happy (1.94).

Keresés

Tananyag ajánló

Holokauszttagadás

"Mindent örökítsetek meg, szedjétek össze a filmeket, szedjétek össze a tanúkat, mert egyszer eljön majd a nap, amikor feláll valami rohadék, és azt mondja, hogy mindez meg sem történt." Állítólag ezt mondta Eisenhower tábornok, miután a saját szemével látta, hogy mit műveltek a nácik a táborokban. A nyugati szövetséges haderők főparancsnoka, a későbbi amerikai elnök jóslata hamarabb beigazolódott, mint gondolta volna. A holokauszttagadók főbb állításai az elmúlt 20 évben már alig változtak. A következőkben a megvizsgáljuk leggyakoribb téziseiket és a történettudomány által használt források - eredeti n [...]

Támogatók

A Társadalominformatika: moduláris tananyagok, interdiszciplináris tartalom- és tudásmenedzsment rendszerek fejlesztése az Európai Unió támogatásával, az Európai Szociális Alap társfinanszírozásával, az ELTE TÁMOP 4.1.2.A/1-11/1-2011-0056 projekt keretében valósul meg.